We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies. Learn more.

What are Grease Traps and How Do They Work?

Nearly half a million tonnes of grease and fat enter the UK sewerage system every year. Grease sticks to pipe walls, which can eventually lead to blockages while fats and oils damage waste water treatment equipment, costing municipalities millions in repairs every year. If allowed to enter a natural water course, fats, oils and grease (FOG) can cause serious damage to the environment.

For these reasons, legislation ensuring that the correct FOG management is used by food service operators is now being heavily enforced. Polluters can face large fines or even closure if FOG waste isn't managed effectively. FOG also causes big problems within commercial kitchens, with FOG from wastewater causing blockages in internal pipes leading to expensive repairs and potential equipment downtime.

Fortunately, grease management systems such as grease traps are readily available. They're often the first-choice FOG management solution for kitchen operators but what are they and how do they work?

What is a grease trap?

Grease traps have been around for more than 100 years and are also known as grease interceptors, converters, catchers, grease recovery / management devices or FOG traps. They're used in in a wide range of environments including:

- Restaurants

- Cafes

- Takeaways

- Pubs, bars and inns

- Hotels

- Schools and colleges

- Bakeries

To put it simply, a grease trap is a receptacle into which wastewater containing FOG flows through before entering a drainage system. The receptacle is designed to intercept or "trap" the FOG while allowing clear water to escape.

Grease trap installed under a sink

How does a grease trap work?

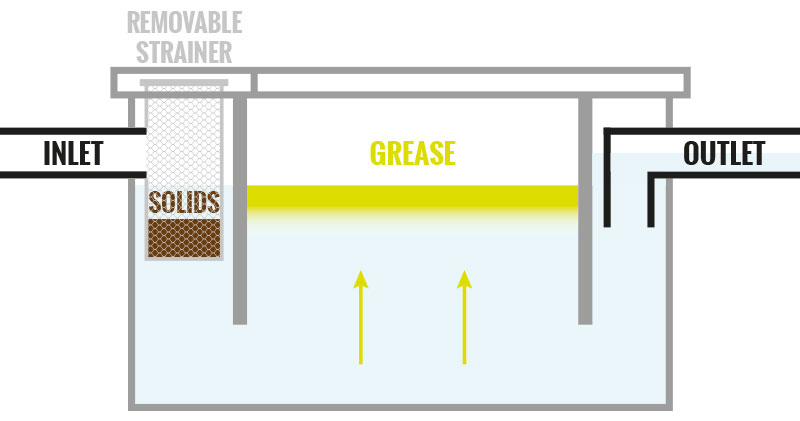

Grease traps work on the basis that animal fats and vegetable oils (grease) are 10 to 15 percent less dense than water and that grease won’t mix with water. Thus, fats and oils float on top of water.

When wastewater enters a grease trap, the flow rate is reduced enough so the wastewater is given enough time to cool and separate into 3 layers. The grease rises to the top inside the interceptor and is trapped using a system of baffles. Solids settle at the bottom and the separated clear water escapes under an outlet baffle. Many grease traps also have strainers for collecting solid debris, which reduces the amount of solids that settle at the bottom of the trap.

Over time, solids and grease build-up, and if left to accumulate for long enough they can start to escape through the outlet and in some circumstances, they can back-up through the inlet. For this reason, the trap must be cleaned / pumped out on a regular basis.

The time between cleaning / pumping out the trap will depend on the amount of wastewater produced and the size of the grease trap but it is usually every 2-4 weeks. This time-period can be lengthened to up to 8 weeks by adding a biological grease treatment fluid into the system. The solution combines non-pathogenic bacteria with nutrients and enzymes to break down FOG, aiding grease trap performance. This process is commonly referred to as “dosing”.

Dosing can also be implemented at the outlet stage as a further method of preventing FOG build-up in internal piping.

The different types of grease traps

There are 3 main types of grease trap; passive hydromechanical (manual), automatic and gravity.

Passive hydromechanical (manual) grease traps

Passive (manual) grease trap

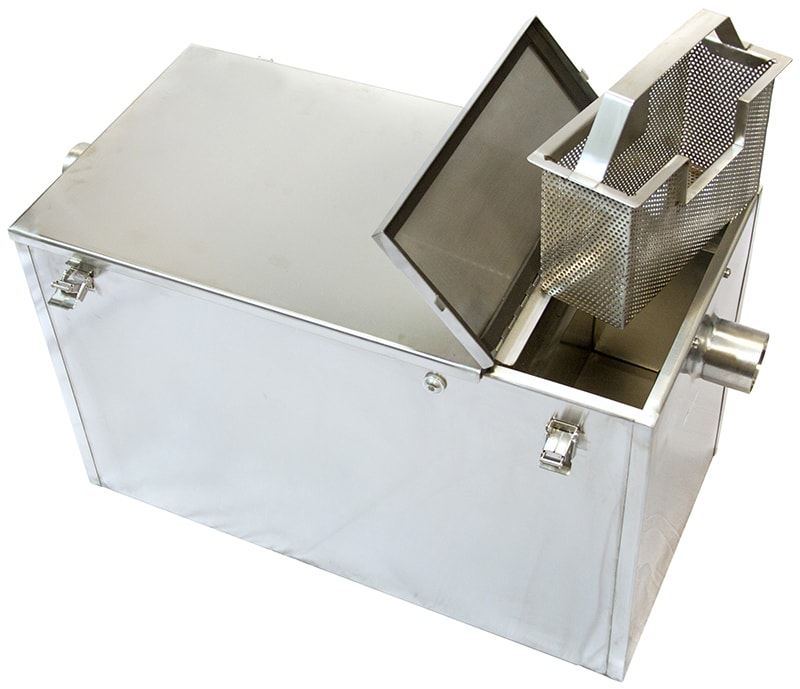

Traditional passive systems are one of the most common systems used in smaller establishments. This is due to the low initial investment cost required to purchase one and the variety of sizes available, meaning they can be easily installed under most sinks while larger units are available to accommodate bigger wastewater production requirements.

Designs of manual grease traps date back to 1885 when the first U.S. patent was issued. Even today grease interceptors use the same basic operating design as the 1885 model. They’re usually constructed from plastic or stainless steel and must be cleaned manually and on a regular basis.

Automatic grease traps

Automatic grease trap

Automatic systems, also known as AGRU’s (automatic grease removal units), use some of the same principals as a traditional passive trap but re-heat and skim out the FOG automatically on a programmed schedule. The skimmed FOG is then transferred into a collector bin for easy removal and recycling. The programmed schedule is based on the amount of FOG produced and means operators don’t have to measure or check grease levels.

Much like passive systems they’re available in a variety of sizes to accommodate a range of requirements. While they have a higher initial investment cost, they are more efficient and have lower long term running and servicing costs.

Gravity grease traps

Gravity systems are usually large in-ground tanks constructed from concrete, fibreglass or steel. They work in a similar way to a passive hydromechanical trap but have a much larger capacity and are better for high-flow applications.

Gravity grease trap

Gravity traps must be pumped out on a scheduled basis, usually by a specialist grease management service company.

With public awareness of environmental issues increasing, looking into your FOG management now is potentially a wise investment and effectively future-proofs your business against future legislation which some are predicting will become more stringent in this area in years to come.

You Might Like

Manual Vs Automatic Grease Traps

We compare Automatic Grease traps with Passive or Manual grease traps for efficiency, sustainability and cost over a three year period, view our results.

The Truth About What’s Really in the UK’s Water Supply

The UK’s municipal water supply is among the best in the world and we all take it for granted, however We examine what’s really in the tap water we drink every day.